North Carolina widow has urgent message about calling 911

CARY, N.C. -- The night of her husband's death, Alison Vroome did everything she thought she was supposed to. She grabbed her phone, called 911, told the operator her address.

Then she told it to her again and again.

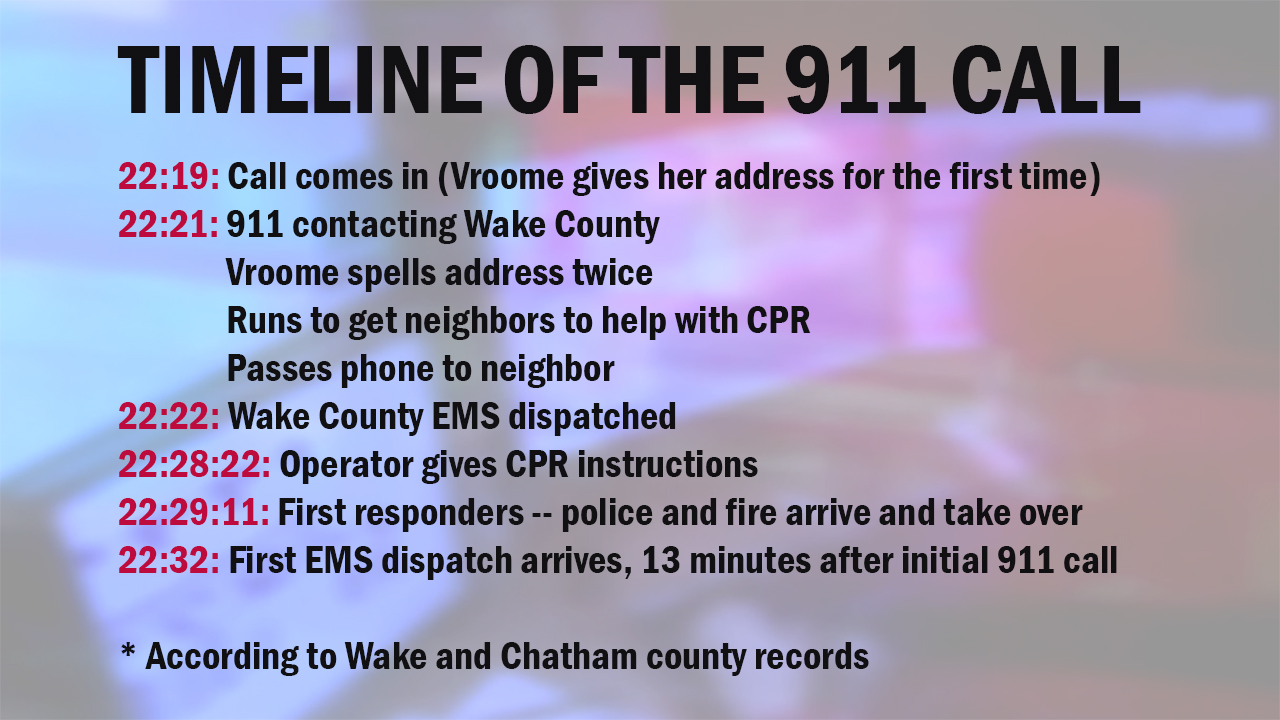

Almost everything seemed to go wrong. The call went to a different county; the operator couldn't understand her address. It was more than 10 minutes into the 911 call before the paramedics arrived, ten minutes of panic that dragged on for Vroome and her family, her two girls crying, the neighbors trying to resuscitate her husband, Kevin, collapsed on the bathroom floor upstairs.

Alison Vroome's husband, Kevin Vroome. (Family photo)

"Are they close?" asked Vroome, four minutes into the call. "We have a rescue squad like one mile from my house. Why aren't they here?"

An ineffective response?

Like anyone calling 911 in an emergency, Vroome, a Wake County teacher, expected her call to go quickly and smoothly. She says she expected the operator to take her call, notify the dispatchers, and EMS to arrive within five minutes. At home, she said she can sometimes hear the first-responder sirens howling down the streets of her neighborhood, so she knows they're located close by.

"That was one of my frustrations that night," Vroome said. "In my panic, I couldn't understand why we weren't getting help faster."

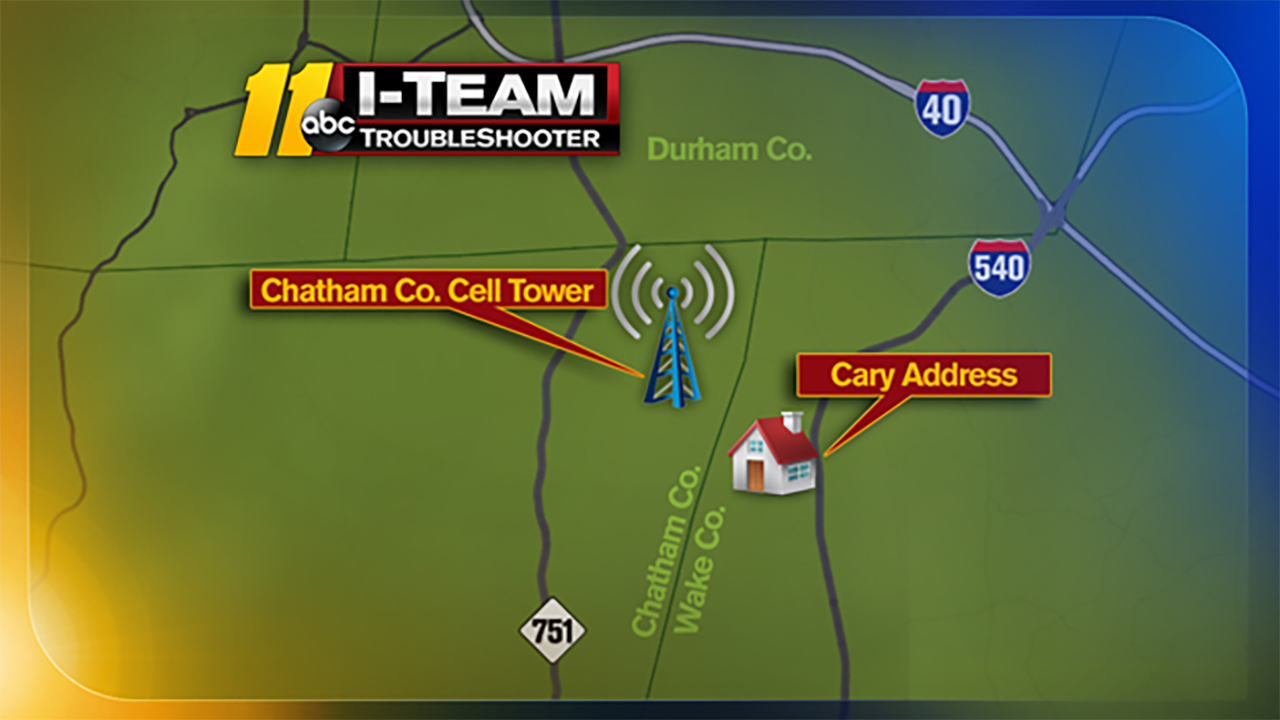

Vroome has lived in a Cary suburban neighborhood for 10 years, within the borders of Wake County. The closest EMS stations to her are located in Wake County, and it would make sense that her phone call would go to the 911 call center located in her county as well.

But when the operator answered Vroome's call that night, it was Chatham County 911.

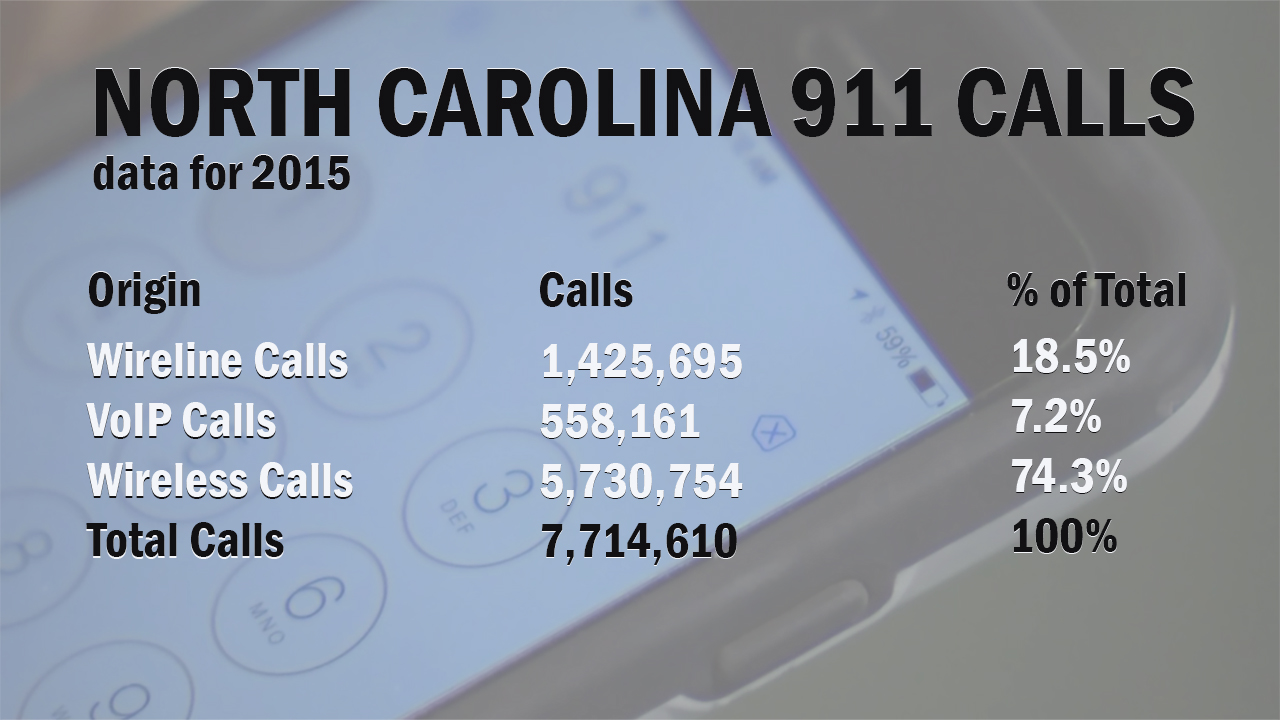

Source: http://it.nc.gov/nc-911-call-statistics

Vroome's call was one of 5.7 million 911 calls that come from wireless phones in North Carolina - about 74 percent of all 911 calls in the state according to data from 2015. Yet 911 call centers are not set up to receive a cell phone's location data. Instead, they receive the location data from the tower pinged by the call - which in Vroome's case was located in Chatham County.

In Vroome's case, an already complicated situation was aggravated by the operator's inability to understand her address.

The operator asked for Vroome's address twice in the beginning of the call. The conversation then veered away from the topic of the address as the operator said her associate was attempting to reach the Wake County dispatch center while she tried to gauge the extent of Vroome's emergency.

On Vroome's side, she couldn't understand why no one was on their way.

"Have you contacted Wake County Cary?" asked Vroome on the call, nearly three minutes in, the frustration and panic evident in her voice.

The operator told her Wake County had been contacted, but she needed Vroome to confirm her address. She repeated it yet again, but the operator still didn't understand. Vroome said it again, this time spelling it out.

The operator told her to calm down and to spell it out one more time to confirm it. After that, she seemed to get it and relay it to Wake County.

Vroome said she believes this is what caused the delay in getting help to her husband.

"It takes going back and forth between Chatham and Wake County four minutes before she comes back to me to say 'spell your address for me,' " Vroome said. "So they never in those four minutes had a correct address even though I was saying the address very clearly."

In the span of those few minutes, Vroome said she was able to reach three neighbors to come start CPR on her husband - it was more than six minutes into the 911 call before the Chatham County operator started giving instructions on how to do chest compressions and CPR.

"I just felt like there was a bit of a failure on the end of 911's call center in getting me appropriate help in an appropriate amount of time," Vroome said.

Chatham County Manager Renee Paschal said she is investigating the call further, but she did admit that the two minutes between answering the call and dispatching EMS was too long.

STATEMENT FROM CHATHAM COUNTY 911 (.PDF)

"In my review of the call, it seems to me that the dispatcher assumed she knew what the street name was and because we didn't have access to Wake County maps we were not able to verify that immediately," she said.

It is that limited access to the maps of another county that is another crucial reason why Vroome says 911 failed her.

A new kind of response system

Vroome will never know if her husband's life might have been saved had EMS arrived sooner. But she said it would definitely have made a difference to her and her state of mind that night.

"It makes me more mad, it makes me just disappointed that the night went down that way, that this is part of our story, this is part of his tragedy, our tragedy," she said referring to the complications with her 911 call. "It just makes it all worse."

Things might have gone smoother if the Chatham County call center had been able to see Vroome's address right away. But unlike a landline, 911 call centers rarely receive the actual location of the cell phone - just the location of the cell tower.

Paschal said this is a statewide issue. County call centers use a detailed mapping system that shows the dispatchers every street and address within their county. However, the CAD, or computer aided dispatch, system doesn't show map details far beyond county borders.

So, when a cell phone call comes in like Vroome's, the operator must rely entirely on the address and directions as given to them by the caller in order to dispatch EMS to the correct place. This reliance can become a serious issue when the operator cannot understand exactly what the caller is saying.

However, there is a movement in the country to implement a new type of 911 call center. It's called Next Generation 911 or NG911.

NG911 is an internet-protocol based system that allows digital information from cell phones to flow between the public, the 911 system, and first responders. Yet while the technology to implement this system is currently available, actually replacing the current emergency response system would be a massive ordeal.

The Vroome family in New York's Central Park. (Family photo)

In a statement released last August, the Federal Communications Commission expanded on the creation of a task force aimed at addressing the most efficient ways states might begin to implement the NG911 system.

The statement outlines what is perhaps the most challenging aspect of transitioning to the NG911 system:

"As public safety authorities are well aware, adopting new technology for public safety can be a double-edged sword; as state and local authorities leverage more advanced technologies, they also must maintain legacy communications capabilities during a transitional period as the larger commercial communications ecosystem migrates to IP technologies. Maintaining two infrastructures increases cost and the potential for life-threatening outages. The longer the transition takes, the more difficult this challenge becomes as the rest of the commercial communications ecosystem moves on."

The data showing how many states have begun to install the NG911 system is incomplete - the data collected by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is dependent upon how many states respond to their survey request. But of the 42 states that have sent their data to the NHTSA, none have fully implemented the NG911 system.

However, according to the NHTSA, about a third of the 42 states have some or all of their states using an IP-infrastructure to process 911 calls - but about half of the states have none.

North Carolina falls amid the states in which regional or local authorities have developed a plan for implementing the NG911 system independent of the state, according to the NHTSA's latest data.

State Rep. Jason Saine, R-Lincoln, was the primary sponsor of a bill passed last session that created a reserve fund to use to install the NG911 system. He said that while North Carolina does have a plan, it will take time to see it through.

SEE FULL VERSION OF HOUSE BILL 730 (.PDF)

"It's a funding issue, but it's also just understanding the technology," he said. "Having enough time to understand what exactly we are going to do to move forward. We have multiple software vendors, you've got different capability from county to county from city to city."

Saine said this is a priority and not an issue that's likely to get bogged down in partisan arguments. Rather, it's an issue of deciding how much money the state is willing to pay for it.

"Folks realize this is something we are going to fund and we have to fund," he said. "This is a critical piece to delivering emergency services in a timely manner. It is an issue of life and death."

Vroome's Message

For Vroome, the most important thing is that no one ever has to have the experience she did when calling 911.

"I would not wish this upon anyone else," she said. "I want people to get emergency care as fast as they can do it. Because when you're in that kind of panicked situation, my personal feeling is that seeing people that are trained to help you show up is the most important and the most comforting thing that can happen. And when that is being delayed, it just makes the situation even more traumatic."

The Vroome family. (Family photo)

Vroome said her husband, Kevin, was a kind, humble man who never wanted to be the center of attention.

"He wouldn't like attention being brought to him but I think he would approve and appreciate the fact that hopefully this can help others and not have anyone else have to go through what we've gone through," she said.

Vroome said she hopes the state will begin the implementation of an updated NG911 system and in the meantime, she said she wants people to be aware of the challenges of calling 911 with a cell phone. Vroome said she hopes parents hear her message and help educate their children. She said she's already taught her two daughters to call from a landline first, then from their emergency security system.

And, as a last resort, from the cell phone.