Ranking today's MLB stars by their Griffey Factor

Thirty years ago today, one swing explained everything. The kid looked a little skinny, and he was a bit twitchy in the batter's box, rocking front to back, front to back, front to back, like a metronome with the weight low on the pendulum. Then a slider hung on the outside corner. The fidgeting ceased. The weight shifted forward. And anyone with an appreciation for baseball or beautiful things or both saw Ken Griffey Jr. swing a bat in the major leagues for the first time and fell in love.

He was 19 years old, facing Dave Stewart, a pitcher whose eyes looked like they could stare into your soul and steal your secrets. Griffey stared right back. On the second pitch, when the ball flew off his bat to the opposite field and one-hopped the left-field fence, Griffey did not need the power of YouTube or Instagram or influencers to be someone. His swing would ensure that.

Well, his swing and his style and the fact that he just looked like he was having more fun than everyone else. Early in his career, when Griffey was like a young superhero finally figuring out the capacity of his powers, he seeded a baseball landscape with all of the attributes that made him Junior -- an inimitable stew of characteristics that built an archetypal baseball player.

Each element can still be found in Major League Baseball's universe three decades later, and it's a testament to the power of Griffey. So, too, is that he remains the standard-bearer for a baseball player who manages to marry extreme fame with equal success. He did that with a dozen qualities, some more important than others and all part of what made him.

While it would be heresy on an anniversary such as this to dare say one individual can be the new Griffey, how about 12? The 12 players in baseball today with a trait close enough to mirroring Griffey that it's worth assessing -- or, as children of the late '80s are wont to do when it comes to Griffey, obsessing.

The mandate, then, was clear: Establish Griffey's defining attributes. Find the players who most embody them. Rank the sameness on a proprietary scale. Most of all, enjoy the stroll from memory lane to the present.

The famous name: Vladimir Guerrero Jr.

While Ken Griffey Sr. wasn't a Hall of Famer like the elder Guerrero, he was a terrific player who played 19 seasons in the big leagues, made three All-Star teams, registered more than 2,100 hits and was a member of the 1975-76 Big Red Machine. Most impressively, he was still active when Junior reached the big leagues, and the Mariners signed him in late August of 1990, Junior's second season. A couple of weeks later we saw one of the great moments in major league history: In the top of the first inning against Angels right-hander Kirk McCaskill, Griffey Sr., batting second, homered to left-center. Griffey Jr. came up next and homered to almost the exact same spot.

Judge Jeff says ...

Pedigree is an enormous part of Ken Griffey Jr.'s buildup and arrival -- and those two elements of his stardom are particularly vital in hindsight. Viral baseball players were rarities. Initially, Griffey's stardom was inculcated through familiarity. Baseball, more than any sport, cherishes multigenerational families, and Griffey was royalty before he stepped foot on the field for the Mariners. Griffey plus the internet plus a far greater mastery of the minor leagues equals Vlad Jr., whose father carries even more cachet than Griffey's: The elder Vlad is a Hall of Famer. It's foolish to foist Griffey-like expectations on Guerrero, but when his oblique heals and he arrives in Toronto, he'll be the talk of baseball.

Griffey Score (out of 5):

Hyped from the start: Bryce Harper

Griffey was the first overall pick in 1987. Harper was the first overall pick in 2010. Both joined losing franchises with no history of success and yet had enormous expectations placed upon them from the beginning. With the hype came criticism at a young age. Manager Matt Williams once benched Harper for not hustling, and when a local columnist called out Griffey for not giving his all, Griffey fired back that "People have no idea why I play. ... I'll never hit 40 home runs." He did hit 40 home runs -- seven times. Harper, so far, has done it just once.

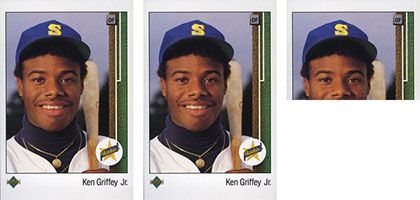

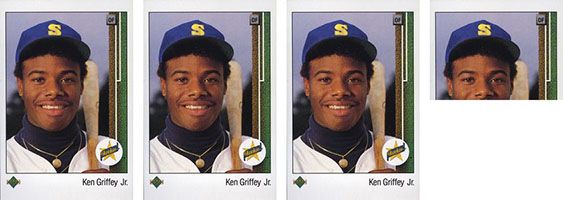

Harper's hype in the internet age is easier to understand. How did Griffey become so popular? A key factor: Baseball cards. In the late '80s, the baseball card boom was still at its peak. The most valuable cards to collect were rookie cards, and when a new company called Upper Deck made the Griffey rookie card No. 1 in its premium, high-quality set, Griffeymania was off and running. As Jeff wrote for Yahoo in 2016, every "middle-class suburban 9-year-old" desired that Griffey rookie card. "It was pure possibility."

Judge Jeff says ...

What made Griffey so notable wasn't his skill or his savoir faire or how damn cool he was. It was the product of all those qualities: his recognizability. Harper is the closest thing to Griffey today in that area. His style is unique, his energy undeniable. There is a particular magnetism about Harper, and even if it doesn't mirror Griffey's -- whereas Griffey was almost universally beloved, Harper is ... not -- it's still ever-present. Griffey's presence demanded attention. Love him or hate him, Harper brings the same feeling to the field.

Griffey Score:

The teenage phenom: Juan Soto

As a 19-year-old rookie, Griffey hit .264/.329/.420 with 16 home runs. As a 19-year-old rookie in 2018 for the Nationals, Juan Soto was arguably even more impressive, hitting .292/.406/.517. In just 116 games, he drew 79 walks, a total Griffey eclipsed just four times in his career.

Both had barely played above Class A or had much minor league experience: Griffey had played 17 games in Double-A with just 552 minor league plate appearances; Soto had played eight games at Double-A with 512 minor league plate appearances. Soto's 22 home runs tied him with Bryce Harper for second most in an age-19 season (behind Tony Conigliaro), but in one sense Griffey's youthful debut season was even more of an eye-catcher.

Before Griffey, the last teenagers to reach even 10 home runs were Conigliaro and Ed Kranepool in 1964 and no teenage position player had played regularly since Robin Yount in 1975.

Judge Jeff says ...

Look, Juan Soto is a stunning talent, and what he did last year -- and what he's poised to do this year and beyond -- is beyond exciting. Even more, Nationals players already swear by him personally, showering him with compliments that have nothing to do with his pristine swing or beyond-his-years plate discipline. And yet as much as his age was part of Griffey's story, his sublimity didn't rely upon it. He was a mesmerizing figure who happened to debut at 19, not someone who was mesmerizing because he debuted at 19.

Griffey Score:

Getting your face in front of the camera: Alex Bregman

Baseball players rarely market themselves like NBA stars. Their social media presence pales in comparison to the biggest names in basketball, and few players seek the media spotlight. One player who doesn't shy away from the camera, who seemingly wants to be the face of baseball, is Astros third baseman Alex Bregman. He's an MVP candidate, nobody plays harder or with more passion, he's smart and interesting and he's on a great team. Still, he has a long way to go to catch Griffey.

Think of the inroads Griffey made into pop culture. Just a few weeks into his rookie season, an entrepreneur named Mike Cramer struck a deal to produce the Ken Griffey Jr. milk chocolate bar. The original run included just 2,500 bars -- many more would need to be produced -- and was made to look like a baseball card, wrapped in gold foil. If you like 30-year-old chocolate, you can still purchase an unopened bar on eBay for $50. In 1992, Griffey appeared in the infamous "The Simpsons" episode "Homer at the Bat," suffering from gigantism after overdosing on brain and nerve tonic. In March 1994, Nintendo released "Ken Griffey Jr. Presents Major League Baseball," the first of four Griffey-branded video games in the decade. He made cameos on "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air" and the movie "Little Big League." In 1996, he became the first baseball player with his name on a shoe when Nike released Air Griffey Max 1.

And who can forget the time Griffey ran for president:

Judge Jeff says ...

As ubiquitous as Griffey was in the early 1990s, there was never any try-hard in his popularity. It came to him, not vice versa. Bregman wants to brute-force his way into people's hearts and minds, which is a perfectly modern way to do it. There's no shame in the game. It's just best to recognize that Bregman's face time is carefully calculated and cultivated while Griffey's, as corporatized as it eventually became, was by and large organic.

Griffey Score:

The smile: Francisco Lindor

The young Griffey played the game with an obvious boyish enthusiasm. As Sports Illustrated's E.M. Swift wrote in 1990, "The pure joy that the kid derives from playing, which, on a good day, can be felt in the far corners of the stands. The way he turns this big-buck, high-pressure business called baseball back into a playground game." It's important to remember this era and why Griffey's style stood out.

The '80s and early '90s were rife with brawls; the '86 Mets had won the World Series while earning a reputation for playing as hard off the field as on it. The A's, the best team in baseball, were led by the brash trio of Jose Canseco, Rickey Henderson and Dennis Eckersley. Pete Rose was suspended during Griffey's rookie season. Barry Bonds, Griffey's rival for best player in the game, was the antithesis of joy.

Griffey's style is best emulated today by Lindor, who always plays the game with a big smile and infectious energy and passion. Like Griffey, he excels at the plate and in the field, and you can't keep your eyes off him.

Judge Jeff says ...

A good set of teeth goes a long way, and a willingness to flash them on the regular only multiplies that. Griffey without an easy smile would've been a horrible tease -- all this natural charisma bottled up behind a stolid facade. His smile was the physical manifestation of the characteristics that made him so irresistible. Now in his fifth season, Lindor hasn't crossed that threshold between hometown popular and nationwide recognizable, although it's not for lack of his teeth trying. They are straight and pearly, and he's not shy with them. His nickname is literally Mr. Smile. And anyone who brings that unadulterated joy onto the field has more than a little Griffey in him.

Griffey Score:

The swagger: Ronald Acuna Jr.

Along with the smile, Griffey arrived with a little youthful swagger -- most notably, with the backward cap he'd often wear in batting practice. Yankees manager Buck Showalter called Griffey disrespectful, although Junior always said he'd simply worn his cap like that since he was a kid when one of his father's caps was too big. A 1994 New York Times headline read, "Griffey's Backward Cap Still in the Forefront." When he hit one of his trademark long home runs, Griffey sometimes took an extra second or two to admire his work. Griffey was good and he knew it.

The best way to describe Acuna: He's good and he knows it. He showboats a little bit. He may flip his bat. After leading off three consecutive games with home runs against the Marlins last year, Marlins pitcher Jose Urena drilled him with a pitch. Acuna would get his revenge:

Judge Jeff says ...

An underappreciated element of Ken Griffey Jr. was just how much he loved him some Ken Griffey Jr. Superstardom doesn't require a healthy touch of ego, but it doesn't exactly discourage it, either. It takes confidence -- or, if you'd prefer, swag -- to willingly roil the establishment with a sartorial choice that goes against everything inscribed in the unwritten rules.

When Acuna arrived in the major leagues as a 20-year-old last season, he refused to let the strictures of the baseball establishment apply to him. It was no accident that MLB's original "Let the Kids Play" commercial cut straight from Acuna to Griffey. The perfect person to embrace letting the kids play was The Kid himself.

Griffey Score:

The showmanship: Javier Baez

From the beginning, Griffey just had "it." He doubled in his first big league at-bat. He hit back-to-back home runs with his dad. He made spectacular catches in the outfield. He was an All-Star Game MVP. He would be talked into entering the Home Run Derby and then win it. He homered in a record-tying eight consecutive games. In 11 Opening Days with the Mariners, he homered seven times. When he finally reached the postseason for the first time in 1995, he homered five times in five games against the Yankees in his first series, including this clutch home run in Game 5 off David Cone:

Like Griffey, Baez has a particular flair when he plays, from his acrobatics in the field to his quick hands on tag plays (who can forget the no-look tag during the World Baseball Classic) to his ability to hit pitches well off the plate for home runs. Griffey had that textbook left-handed swing while Baez relies on pure bat speed, but both players bring that something special that goes beyond the raw numbers.

Judge Jeff says ...

There's a fair bit of Griffey in Baez, simply because so few players combine overwhelming amounts of creativity and skill. Griffey did things no one else could; Baez does things no one else can. At the same time, Baez's showmanship doesn't evoke Griffey's lineally. It's almost evolutionary, an objection to the norms that were established in the previous generation, when Griffey was playing. Were he in his prime today, Griffey might feel more emboldened to be showy, the game being what it is. As it stands, though, Griffey and Baez aren't a perfect match because of the generation gap.

Griffey Score:

Signature plays in the field: Nolan Arenado

Arenado can do this:

While Griffey could do this:

And this:

Griffey won 10 Gold Gloves. Arenado already has won six in his first six seasons. Who do you have?

Judge Jeff says ...

Here's the problem: There's nothing inherently unique about the fielding prowess of Griffey and Arenado. Both are spectacular at their position. Their ability to slacken the jaw of anyone watching is a neat party trick. But there are plenty of incredible fielders with the talent to wind up on highlight shows nightly. That's cool. That's great. That's just not something isolated to Griffey and Arenado.

Griffey Score:

Unrivaled power: Aaron Judge

We don't have Statcast data from Griffey's career, but safe to say that Griffey would have fared just fine in exit velocity and barrels. Griffey hit a lot of towering home runs and certainly took advantage of that short porch in the Kingdome (although unlike Judge at Yankee Stadium, Griffey had to contend with a 23-foot high wall in right field and right-center). If you doubt Griffey packed Judge-like raw power, well, take a look at this mammoth blast in Toronto:

Judge Jeff says ...

It's probably fair to say Griffey didn't have the most power of his era. That title belonged to Mark McGwire. But tape-measure home runs of all manner and variety hold a place in the hearts of fans, and the knowledge that every single Ken Griffey Jr. at-bat could wind up with a ball parked 450 feet away made his at-bats that much more titillating. Judge is like a mash-up of McGwire and Griffey -- Herculean power reinforced by the power of pinstripes. He is a star because of the power; he is a brighter one because he is a New York Yankee.

Griffey Score:

Sweet lefty swing: Cody Bellinger

Griffey always called himself a line-drive hitter who hit home runs, but I don't think that is exactly accurate. When he first came up he did spray the ball all around, but he soon morphed into what we would now label a launch-angle guy.

In his first four seasons, he had a ground ball-to-fly ball ratio of 0.73. Over the next eight seasons, when he averaged 44 home runs per season, that ratio was 0.52. He did it with that picture-perfect left-handed swing, starting from an upright position and whipping the bat through the zone with that beautiful uppercut swing and long, one-handed follow-through.

Carlos Gonzalez has a pretty swing he patterned after Griffey, but he also may have a .640 OPS in Columbus, so let's go with Bellinger. The 23-year-old Dodgers outfielder/first baseman may be the young lefty hitter with the most potential to one day hit 50 home runs. He hit 39 as a rookie before falling off to 25 last year, but he is off to a strong start with five home runs so far. Bellinger's swing doesn't exactly resemble Griffey's, but he also starts upright, although with the bat flat behind his head and he uses his legs more to drive the ball in the air. Worth noting: Griffey's first 40-homer season came in his age-23 season.

Judge Jeff says ...

This may be controversial, and that's fine. I'll argue until I'm blue in the face that as much as it was the backward hat and the power and the catches and the commercials, what sold so many people on Griffey was the swing. It is universally recognized that left-handed swings look prettier than right-handed swings. Still not sure why. Don't really care, either, because ignorance, in this case, allows me to watch a GIF of Griffey swinging approximately 200 times and not feel guilty or weird. Fine. Maybe it's a little weird. But it's so pretty. The aesthetics of Griffey's swing -- the just-right leg kick, the smooth bat path, the uppercut finish -- are nonpareil.

The closest thing to it today is Bellinger. He takes a slightly bigger stride. He flexes his wrists slightly as the ball is traveling to the plate. He finishes with two hands. It's still gorgeous -- a marvel of bat speed, strength and desire to lift the ball and drive it untoward distances. When Bellinger connects, he is capable of unleashing majestic, exalted home runs that look like they're trying to climb to heaven -- or at least the upper reaches of Rogers Centre.

Griffey Score:

All-around ability: Mookie Betts

Griffey hit 630 home runs, but was obviously much more than just a power hitter. Like Betts, he could do everything well (at least in the first half of his career before all the injuries in Cincinnati): Hit, hit for power, run, throw and field. During his 10-year peak with the Mariners from 1989 to 1999, he hit .302, including .300 seven times. Griffey wasn't a blazer, but was fast enough to average 15 steals per season through age 29 -- and he could turn on the jets at the right moment:

Maybe the best comparison between Betts and Griffey is both have that natural instinct for the game, to see the game unfolding before it happens. Betts isn't the fastest guy either, but gets great reads on the ball and his arm may actually be better than Griffey's. He's 110 for 132 as a base stealer and now owns a .302 career average after leading the AL with a .346 mark in 2018. Griffey never hit .346 -- but Mookie probably won't ever hit 56 home runs.

Judge Jeff says ...

It's scary how similarly productive they are -- in his first five years Griffey slashed .303/.375/.520 while Betts was .303/.370/.518 -- when they're actually quite different players. Griffey was a baseball player birthed from a blueprint: 6-foot-3, 200 pounds, long, lithe, agile. Betts is a different sort of athlete: six inches shorter, 20 pounds lighter, powerful beyond what he should be. He's great, and he's probably going to be $300 million great, but Dave's point about ceiling matters: A number of players can reach 30-something home runs, a handful 40, but even Betts' greatest supporters can't fathom him reaching 50, which Junior did in back-to-back years. He's still awesome, amazing, every adjective in the thesaurus. And although wins above replacement may argue otherwise, he's still not Griffey -- not yet.

Griffey Score:

Best player in the game: Mike Trout

Throughout the '90s, Griffey was generally saluted as the best player in the game, a tribute that irked Bonds to no end. Griffey won one MVP award, in 1997, when he led the AL with 56 home runs, 147 RBIs and 125 runs while batting .304. We didn't have WAR back then, but Baseball-Reference.com retroactively values Griffey as the best position player in the AL in 1993, 1996 and 1997; second-best in 1991 and 1994; and fifth in 1998.

Bonds, however, had an argument. During the '90s, Baseball-Reference credits Griffey with 67.5 WAR and Bonds with 80.2. He had the highest WAR in the NL seven times (and all that was before his insane run from 2001 to 2004 when he broke the game). Bonds hit .302/.434/.602 with 361 home runs in the decade; Griffey hit .302/.384/.581 with 382 home runs. Bonds' big advantage in statistical value was 50 points of on-base percentage. But Griffey was more popular and played center field and ran for president.

As for Trout, his big advantage over Griffey is the same as Bonds: He gets on base more often, with a career .417 OBP (in an era where runs are harder to come by). Like Griffey, Trout is likable and plays center field. Maybe the major difference between the two -- and this isn't a knock on Trout -- is that Griffey just had that undefinable "it" factor. Maybe that isn't fair to Trout. Griffey, after all, was of his time and for a certain generation of baseball fans there will never be another player like him.

Judge Jeff says ...

We're talking about Ken Griffey Jr. three decades later because he was the best, right? He played in the steroid era -- and apparently clean at that -- and somehow still managed to distinguish himself. Almost the entire second half of his career was an injury-riddled disappointment -- and he still maintains a bordering-on-religious reverence from fans who grew up watching him. The way people talked about Griffey -- they do that about Trout now, only more. It's a gift to get to watch the most talented players of a generation knowing they will eventually rank among the best of all time. As few great fielders as there are, and with fewer great power hitters in circulation, the idea that one player can provide both separates him. And that's Trout -- a world away from everyone else because he's really that much better. Figure out how to sell him to the masses and he may be the first five-card Griffey match.

Griffey Score:

Related Video

Related Topics

- SPORTS

- ESPN

- ATLANTA BRAVES

- NEW YORK-YANKEES

- PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES

- CODY BELLINGER

- WASHINGTON NATIONALS

- BOSTON RED-SOX

- CINCINNATI REDS

- MOOKIE BETTS

- MIKE TROUT

- COLORADO ROCKIES

- LOS ANGELES-DODGERS

- JAVIER BAEZ

- RONALD ACUNA-JR

- NOLAN ARENADO

- CLEVELAND INDIANS

- AARON JUDGE

- ALEX BREGMAN

- MLB

- KEN GRIFFEY-JR

- FRANCISCO LINDOR

- HOUSTON ASTROS

- JUAN SOTO

- SEATTLE MARINERS

- LOS ANGELES-ANGELS

- VLADIMIR GUERRERO-JR

- CHICAGO CUBS

- BRYCE HARPER